Since the 19th century, ancient Egypt has been one of the most “exotic” cultures to admire for those in the western world. As it is a civilization of great, almost unprecedented technological and architectural advances, it has been the object of great scrutiny for scholars for centuries. Popular culture seemingly embraced this almost mystic attitude towards ancient Egypt in many films over the years, my favorite being in the movie Stargate. It is a sci-fi thriller starring James Spader, and as cheesy as it can be at times (as any sci-fi can be), I thought it was an interesting and thought provoking film. In Stargate, ancient Egyptian religion and culture are represented in a way that draws from actual ancient Egyptian fact, yet puts a “Hollywood” spin on it per say.

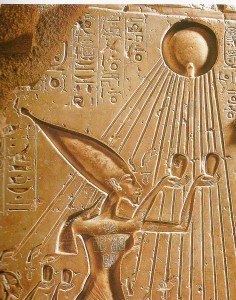

The first representation in Stargate that I wished to address is that of the Egyptian sun god Ra. In the film, Ra is an alien creature that dominates humanity and uses them to continue to sustain him for thousands of years. He is portrayed as androgynous, having the features of both a man and a woman, which may actually have some precedent in ancient Egyptian culture. As studied in my Religion of the Pharaohs class, Hatshepsut was often depicted in art with the features of both a man and a woman. But were these done for the same reasons? In my opinion, the androgyny of Ra is related to Hatshepsut, but also it is done in order to communicate to the viewer how different Ra truly is as a different species than human. These androgynous features accentuate how different and alien he is in both senses of the word.

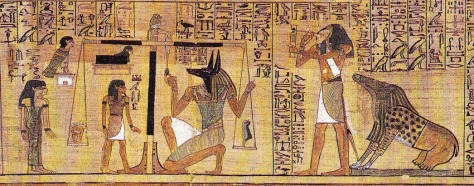

Another representation that I thought was fascinating in Stargate was that of the traditional Egyptian sarcophagus. In ancient Egypt, the sarcophagus was extremely important in the process of proceeding to the afterlife, as it served as something like a passage or gateway in the rituals of preparing a person for the afterlife. Yet, the representation in the movie takes it a step further, showing that the sarcophagus can actually restore life to those dead. Though the representations may be different, what remains the same is how necessary the role of the sarcophagus is, either for attaining afterlife, or maintaining life. The role of the sarcophagus is prominent in ancient Egyptian culture and religion, exemplified by its indelible role in the plot line of the film (saving the life of Daniel’s wife).

The last representation I wished to discuss from the film is also the most far fetched in my opinion. Pyramids in Stargate were giant docking stations for Ra’s enormous spaceship. As studied in my class, pyramids had everything to do with the afterlife, being built on the west side of the Nile (West represents afterlife) as places of eternal worship for whichever pharaoh built it. This representation does not seem to have any cultural or religious significance when discussing ancient Egypt.

However, when relating how pyramids are depicted in the movie, when analyzed in comparison to contemporary cultural issues there is much to say! Depicting pyramids as “alien” may be meant as a post-colonialism mockery on the history between Britain and modern Egypt. Therefore maybe making things look alien and foreign with Ra and the pyramids might just be a way to make ancient Egypt look exotic and exciting, or it may also be a satirical mockery of the colonial attitude. I believe this is supported by the overall plot of the movie, as it is a slave revolt against a power thought to be too great to overcome. The natives, in this case, signify Egypt as a small powerless colony breaking away from Ra, the exploiting tyrant which signifies Great Britain.

Overall, the different representations of ancient Egyptian religion and culture in the film Stargate paint a very different view than what fact has us believe. Some of these changes maintained roots in ancient Egyptian fact, such as the representation of the sarcophagus, yet others were made seemingly nonchalantly in order to either put a “hollywood” spin on the story or to attack a contemporary issue such as the aftermath of colonialism. As there is so more to the film than what I was able to analyze here, I encourage anyone who is a true lover of ancient Egypt (or sci-fi) to watch the film themselves and see what conclusions they find!